Palace of Transportation: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| (2 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 21: | Line 21: | ||

| special_day = | | special_day = | ||

| other = | | other = | ||

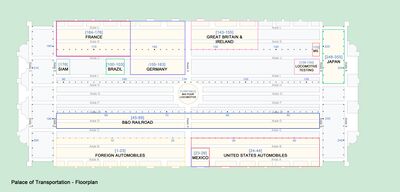

| floorplan_image = FP-Palace of Transportation.jpg | |||

| ticket_image = | |||

}} | }} | ||

With an obvious train station vibe, the '''Palace of Transportation''' stood west of the [[Palace of Varied Industries]] and north of the [[Palace of Machinery]] as part of the [[Main Picture]]. | With an obvious train station vibe, the '''Palace of Transportation''' stood west of the [[Palace of Varied Industries]] and north of the [[Palace of Machinery]] as part of the [[Main Picture]]. | ||

==Before the Fair== | ==Before the Fair== | ||

| Line 98: | Line 99: | ||

==See also== | ==See also== | ||

[[German | [[German Railway Exhibit]] | ||

[[Aerodrome]] | [[Aerodrome]] | ||

Latest revision as of 05:30, 14 December 2022

| |

| Location | Main Picture |

|---|---|

| No. of Buildings | 1 |

| Construction | |

| Construction Cost | $684,608 ($20.6 million in 2021) |

| Architecture | |

| Architect | E. L. Masqueray |

| Dimensions | 525' x 1,300' |

| |

With an obvious train station vibe, the Palace of Transportation stood west of the Palace of Varied Industries and north of the Palace of Machinery as part of the Main Picture.

Before the Fair[edit | edit source]

The floor area is spanned by wooden trusses. The sum of $10,000 was expended for hoisting apparatus before one of the 220 trusses of the Palace of Transportation was lifted from the ground. These trusses were raised in rows of five making a complete cross section. The end trusses are one hundred and five feet in span. The three center trusses are one hundred and one feet long. The weight of each truss is about fifteen tons. Beginning at the eastern end of the site the twenty horse power engines raised these trusses from the ground and placed them upon the supporting columns. The engines were moved westward as row after row of trusses was placed. The eastern end of the Palace was completed before the western end was raised. It was possible to see in the 1,300 feet of length all stages of construction from first footings to finished facades. The building of the Palace of Transportation was one of the most interesting spectacles of the construction period. There were times when the building grew with marvelous rapidity. In one week forty trusses were lifted to their places. No steel trusses were employed. Wonderful results from the builder’s point of view and entirely satisfactory conditions for the exhibitor’s needs were wrought with wood. The nails driven home weighed eleven thousand tons. In the construction of the Palace of Transportation there was used the enormous amount of 12,000,000 feet of lumber.

Description[edit | edit source]

Built by Chicago's H. W. Schlueter, the Transportation palace was one of the last of the colossal edifices to be constructed for the Fair, the immense building covered 15.6 acres. Sixty foot high entrance arches lead to east end 14 indoor railroad tracks which ran the entire span of the building. The palace marked the 100th anniversary of the invention of the steam locomotive. In this building will be found every known means of conveyance, from the old-time stage coach and the first steam engine to the very latest contrivances in air-ships, automobiles, and motor cycles. Full trains of cars, consisting of palace, observation, dining, drawing-room, bridal, sleeping, day, and baggage cars, with the very fastest engines, will be on exhibition ; also the very latest surface street cars. Models of the fastest steamships and river craft, in working order, together with every description of saddlery and harness, will be found here.

At the corner is a symbolic figure holding in one hand a miniature steamship. This piece of statuary stands over fifteen feet. It is unique in that it is the only one of the eight great palaces in the group in which the designer has not employed what are known as the classic orders of architecture. The three great arches enclose a vast porch. They are separated by strong pylons the summits of which are richly decorated.

Statuary—Transportation by Rail and Transportation by Water, beautiful seated female figures by George J. Zolnay, flanking east and west entrances. Shieldbearers, by H. Wiehle, repeated over each of arches at east and west fronts. Other figures representative of Transportation are by F. H. Packer, Wm. Sievers and F. F. Harter.

The toilet rooms were placed in the bases of the projecting pylons, and arranged to receive light and ventilation, and to be accessible from the exterior, so that no exhibitors were annoyed by being placed in the neighborhood of plumbing conveniences .

The major theme for the Palace of Transportation (as with the entire Fair), was Life and Motion.

The centerpiece exhibit of the grand palace was the American Locomotive Company's display of a 160 ton engine and coal car. Mounted on a massive revolving turnstile, it was named The Spirit of St. Louis.

Inside, the palace harbored an enormous mixture of historical and state of the art forms of transportation. The displays varied from the time of the stage coach to the era of the 'modern' car, varying from the simple to the palatial.

Chief of the Department of Transportation, Willard A. Smith wrote "Transportation is the life of modern civilization." The Department gave the Fair 200,000 dollars to develop and demonstrate aviation at the Exposition. The palace displayed a multitude of the latest means of travel. Though the automobile was still in its infancy, there were 160 on display and even to purchase. Fairgoers could view the latest trains and water craft. The American Street Flushing Machine Company showcased their street cleaning machines and fairgoers could marvel at sections of tunnel, steamships, gliders, motorboats and aviation. The Pennsylvania Railroad displayed a huge detailed 'model' of New York Central Station, while other models of stations from St. Louis and Washington DC were shown.

Locomotive Testing[edit | edit source]

In the western end of the building, the Pennsylvania Railroad Company, The Pennsylvania Lines West of Pittsburg supplied a laboratory for testing the efficiency of locomotives. Supervised by F. D. Casanave, the array of tests were extensive, the results were calculated in a 'computing room' to keep pace with the development of observed data in the laboratory. The data was presented in three different relations:

1. The performance of the locomotive as a whole, under which relation general comparisons will be based on work developed at the drawbar.

2. The performance of the boiler.

3. The performance of the engines.

Tests of locomotives have been conducted through the period of the Exposition and the results carefully analyzed. Water is weighed. Coal is measured. The engineer and the firemen are in their places. The test is on. Faster and faster run the wheels until a speed of eighty miles an hour is reached. The racing on the elevated tracks continues the appointed time. Then the great machine slows down. Note is taken of remaining water and fuel. The ash is examined and weighed. The record is entered. There is a different test. Steam is raised. Tracks are sanded. The start is made. More steam is applied. Not a foot does the monster move. The pull is against a dynamometer. Slowly the register rises until it shows the pulling record at full power. The details of the tests speak for the scientific importance. Water for the steam is tested to establish its purity. The coal is analyzed to determine its steam making quality. The flue gases even must undergo chemical investigation. While visitors stand within a few feet these tests of speed, as shown by the revolving wheels, are pushed to more than a mile a minute. Twenty days is given to testing each locomotive.

Notable Displays[edit | edit source]

On a steel turn-table a mighty locomotive of over 200,000 pounds weight, its wheels revolving at great speed, turns slowly, throwing its electric headlight to the remotest exhibit of Transportation.

San Francisco brought in the first street car (1873), ever used.

Hayes-Apperson displayed the first ever gasoline-run automobile (1893). Young companies: Ford, Studebaker, Rambler and Oldsmobile all has displays. France, the world's leading manufacturer of automobiles at the time had an exhibit that almost exclusively devoted to them. Fulton and Walker Company displayed a number of ambulances, while fairgoers could view the latest in hearses. The John Deere Plow Company displayed the latest buggies.

As a bizarre oddity, one company displayed a dried but still pungent leather skin of 'Rajah', the famous elephant from Ringling Brothers Circus. In 1900, the elephant contracted a disease called musth and killed seven men. The beast was too powerful to be killed by poison and guns, so they dynamited the animal. Besides the hide, a display depicting the history of Rajah in pictures brought in a multitude of the curious.

Another display was Dr. Bircher's War Museum, from Aarau Switzerland, whose relief maps full illustrated all the American wars.

The United States featured many yachts, work boats of all types and a historical display of navigation along the Mississippi River.

Because President McKinley was assassinated in 1901, the Fair built a secure railroad line straight through Forest Park and into the Palace of Transportation. This route would allow President Theodore Roosevelt to access to the Fair (and a quick exit if trouble ensued).

Gallery[edit | edit source]

-

Brazilian Exhibit

-

Westinghouse stand in the Russian exhibit

-

Means of transportation in history

-

History of the Engine

-

First Engine

-

Early locomotive engine

-

The Northwest Pioneer

-

First coach train

-

German train to set the record of 100mph

-

Section of the New Jersey Tunnel

-

$20k steam launch

-

Automobile Exhibit

-

Carriage Exhibit

-

Foreign Automobile Display

-

Northwestern Military homemade automobile